Editorial Note: I am so excited about the next topic that I had to split it across two posts. For Part 1, I introduce the idea that, while expertise is great, there is a cost associated with it. In Part 2, I will talk about the origin of research on expertise and its educational implications. Let's jump in with a real mind scrambler!

The Backwards Brain Bicycle

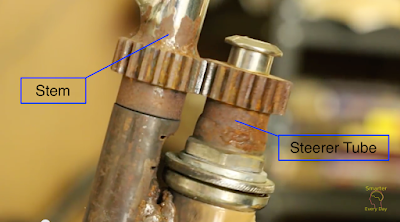

Grab a junky bike and pull the handlebars and stem out of the steerer tube. Next, weld one gear onto the steerer tube and another gear onto the stem (the stem is the piece connected to the handlebars). Once you're done, it should look like this:Due to your modification, when you turn the handlebars to the right, the front wheel pivots to the left (and vice versa). Before you embark on your maiden voyage, what do you suppose will happen? If you're not sure, take a look at this fascinating video.

What happened to this poor engineer? Why did it take him eight months to learn how to ride his "backwards brain bicycle"? The answer to that question is related to why a softball pitcher can reliably strike out the best batters from Major League Baseball (MLB).

"Swing and a miss" --Harry Doyle

In MLB, there is a distance of exactly 60.5 feet between the pitcher's mound and home plate. When a pitcher throws a 95 mph fastball, the ball arrives in a little less than half a second (.43 seconds, to be precise). That means the batter needs to decide whether he should swing (or not) in about a quarter of a second. Otherwise, the ball will blow past him as he stands there and ponders whether he should swing.Because it truly is a split-second decision, the batter must look for an edge. One place to find an edge is to move upwards in the stream of events and find a reliable cue for swinging. One of the cues that batters use is the pitcher's grip on the ball. If they hold it with two fingers over the top, then it is a fastball. If they put more distance between their forefinger and the thumb, then it will be a curve ball. The other cue that batters look for is the spin on the ball, which transmits itself as a certain "color" of pitch.

MLB players log thousands of hours behind the plate trying to hone their batting ability. In effect, they become experts in watching, categorizing, and reacting to a variety of different pitches. So if they truly are expert batters, then why can softball pitcher Jennie Finch strike out batting legends Barry Bonds and Albert Pujols? [1]

The explanation is fairly simple. Expertise is highly narrow. When faced with a typical softball pitch, MLB batters are watching for something that will never come. They've essentially wired their brain to perceive and react (without much conscious intervention, mind you) to a highly narrow band of stimuli. Because overhand pitches used in MLB tend to fall, the batter watches for a ball that starts high and gets pulled to the ground. A softball pitcher throws underhand, so the ball starts low and has the possibility of rising. They also are watching for the aforementioned cues of the pitcher's grip and the spin on the ball, but the grip that a softball pitcher uses is completely different. By changing the narrow band of stimuli that a batter is trained to read, you can essentially reduce and expert batter to a novice, or possibly even worse.

But let's stop talking about muscular expertise. What about conceptual expertise? Are there any hidden costs there?

Looking in All the Wrong Places

Another way in which expertise can steer a person wrong is by biasing her to look for solutions within the prescribed content area of her specialty. Consider the following experiment [2] where baseball experts were given a creativity test called the Remote Associates Test (RAT). Their job was to look at a list of three words and figure out what single word binds them together. There were multiple experiments and conditions in the original study, but the one relevant to the current discussion was between lists of words where the domain knowledge was relevant and applicable and a different list of words where the domain knowledge was irrelevant and misleading.To make this concrete, suppose you are a baseball expert, and I give you the following three words:

Baseball-Relevant: WILD DARK FORK

What word connects these three? A baseball expert might answer PITCH (e.g., wild pitch, pitch dark, and pitch fork). The word "pitch" comes straight out of baseball, and it is therefore relevant to the solution to this RAT problem. When solving baseball-relevant problems, baseball experts had an accuracy rate of about 38%. This was roughly the same accuracy rate among baseball novices, who identified the connecting word 40% of the time.

But then the experimenters switched things up and gave baseball experts and novices a list of words that seemed like they might be connected to baseball, but ultimately they were not connected. Here is an example:

Baseball-Irrelevant: PLATE BROKEN SHOT

What single word connects these three [3]? The first two words seem to hint at HOME (e.g., home plate and broken home), but then HOME doesn't really go with the last word (what is a home shot or a shot home?). How do you think the experts did? Their performance plummeted. Their accuracy rate dropped by over half, to 15%. Baseball novices didn't show the same drop in their performance; in fact, they showed the same accuracy rate of 40% on the baseball-relevant and irrelevant tasks.

What's going on? Why can't baseball experts suppress their knowledge? Even when the experimenters warned them that baseball knowledge was irrelevant, they still couldn't turn it off. They seemed to be biased towards looking for solutions that are aligned with topics that they know a lot about, which actually interfered with performance when the solution was not aligned with their area of expertise. What may also be surprising is that the experts, at least for this task, did not out-perform their novice counterparts. In my next post I will explore situations in which being an expert can help, or hinder, performance, depending on the task at hand.

That concludes Part 1 of The Downside of Expertise. Check back next week for the conclusion and the connection to education!

Share and Enjoy!

Dr. Bob

For More Information

[1] Why MLB hitters can't hit Jennie Finch and science behind reaction time. Sports Illustrated, Volume 119, Issue 4. (July 29, 2014) [link] [video][2] Wiley, J. (1998). Expertise as mental set: The effects of domain knowledge in creative problem solving. Memory & Cognition, 26 (4) 716-730.

[3] The word that binds PLATE, BROKEN, SHOT together is GLASS.