Learning By Doing

Let’s start by doing a challenge. (Full disclosure: if you end up not finding this exercise challenging, it’s because I typically do this with middle-school students!)

Here we go:

Google a map of North Africa. Then, study the country that’s to the west of Egypt for 10 seconds. Next, study the country that’s south of Egypt for 10 seconds.

Close that tab!

Count to 20.

Now, test yourself. Are you able to recall the names of the countries to the west and to the south of Egypt?

Given the short duration of time that passed between you learning the names and then being quizzed, you were likely successful in getting them both right! However, what if I asked you to retrieve that same information again in 3 hours? How about tomorrow? Or in a week? Or in a month?

“Hoping to find some old forgotten words…” —Africa, Toto

At this point, you might have realized that we’re revisiting some topics that have previously been discussed on this blog: forgetting and how one might combat it.

In those posts, Dr. Bob explained:

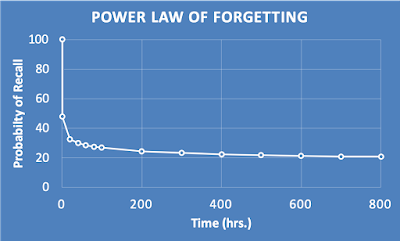

“Forgetting is non-linear, meaning it decays quickly and eventually slows down.”

Visually, he also provided a forgetting curve that shows how fast we forget newly learned information:

The good news is that we can combat this forgetting through retrieval practice, where recalling that information from memory strengthens the stickiness of that information and slows the rate of forgetting.

To take it one step further, those blog posts referenced another article from Duolingo’s blog that expanded on the optimal cadence for retrieval practice. At Duolingo, they utilize the spacing effect [1], and they use their vast amounts of data points to map out a model of when students should review certain vocabulary words based on their prior performance [2]:

Research shows that the optimal time to retrieve information is right when you’re about to forget it [3]. Because each retrieval practice should increase the durability of that memory, the retrieval practice is spaced out with longer and longer lag times in between each session. Practically, this has the positive effect of increasing studying efficiency because at any given moment, you can focus only on the subset of content you’re most about to forget.

The Classroom Connection

I taught 8th grade math for two years from 2013 - 2015.

As a first year teacher, I was overly focused on just making it through the large amount of content that was mandated by our state curriculum. I gave little time or thought to review, and overall, my classroom looked a lot like the one that Dr. Bob described:

“The traditional method of teaching is to introduce a topic, solve a few illustrative problems that relate to that topic in class, assign some homework problems, and then give a test a few days or weeks later to see if the students retained the material. For highly important topics, the same items might make a reappearance on the final exam.”

Dr. Bob also describes the problem with this traditional approach:

“...if a topic hasn't been discussed in several weeks, then it is likely the memory system is going to treat that memory as unimportant, and it will find itself on the fast side of the forgetting curve. Second, if too much time elapses between the presentation and evaluation, then the probability of successful recall is going to be very low.”

I had never heard of the forgetting curve, but I saw it working in full force with my students.

In my second year, I resolved to provide more review opportunities. Overall, however, I was still completely ignorant to the basic principles of learning science. I didn’t know that retrieval was the most effective way to review. When I myself was a student, I was a serial crammer, so the spacing effect was basically foreign to me.

As a result, review in my classroom was often suboptimal. For example, I occasionally asked my students to just re-read their notes. I would sometimes put questions covering older topics on students’ homeworks or quizzes, but certainly not with enough consistency to make it stick. To make matters worse, it was a massive challenge to figure out which topics most needed review. Some of my students needed to review fractions at certain points of the school year, while others really needed to review solving integer operations.

That year, my students performed better than the previous year, but continued to struggle to effectively retain information that they had learned.

A few years later

A couple years later, I made a career change and became a software developer. Around that time, I read a book called Make it Stick by Roedinger, McDaniel, and Brown [4], and I was blown away.

This book was the first time that I learned about the basics of learning science. The book went through the nuances of how we learn and retain information, and it provided definitive recommendations on research-backed practices that educators should be using in their classrooms, like retrieval and spacing.

My mind immediately flashed back to my classroom, where these best practices could have made a substantial difference with how my students learned. I also realized that this issue went further than just my own classroom. By that point, I had sat through countless hours of teacher professional development, and I also had a master’s degree in education. However, not once did we cover those basic cognitive science principles on how students learn.

Now

Those experiences were the inspiration for Podsie, a nonprofit edtech I co-founded that’s focused on improving student learning and empowering teachers by making the science of learning more accessible.

At Podsie, we’ve built an online web app for teachers and students that makes best practices like spacing, retrieval, and interleaving easy to implement in the classroom. With Podsie, a teacher creates an assignment that assesses the content that students learned. When students complete a question on an assignment, the question goes into that student's personal deck, which essentially represents the entire body of knowledge that a student should know for that class.

Each student's personal deck is powered by a spacing algorithm that determines when the student should review a question again, similar to how Duolingo prompts students to review a vocab word when they are just about to forget it. Overall, this ensures that students have a personalized review experience that allows them to focus on concepts they most need to review.

All in all, we are incredibly excited to make it easier for teachers and students to utilize and learn more about learning science best practices. On the way, we’ve had the privilege of learning from and working with cognitive scientists like Dr. Bob who are on the same journey to ensure students and educators can be the best they can be.

We launched a beta trial of our app in August of 2020, and we’re preparing to launch in June of 2021. Our app is free for teachers and students, and if you’re interested, you can sign up on www.podsie.org to be notified as soon as we’re live!

Going Beyond the Information Given

[1] Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological bulletin, 132(3), 354.

[2] Figure 3 is taken from https://blog.duolingo.com/how-we-learn-how-you-learn/, which was originally published in their academic paper:

Settles, B., & Meeder, B. (2016, August). A trainable spaced repetition model for language learning. In Proceedings of the 54th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics (volume 1: long papers) (pp. 1848-1858).

[3] Landauer, T. K., & Bjork, R. A. (1978). Optimal rehearsal patterns and name learning. In M. M. Gruneberg, P. E. Morris, & R. N. Sykes (Eds.), Practical aspects of memory (pp. 625-632). London: Academic Press.

[4] Brown, P. C., Roediger III, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick. Harvard University Press.